Sensory processing disorders (SPD) are more prevalent in

children than autism and as common as attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder, yet the condition receives far less attention partly because

it’s never been recognized as a distinct disease.

Pratik Mukherjee, MD, PhD

In a groundbreaking new study from UC San Francisco, researchers have

found that children affected with SPD have quantifiable differences in

brain structure, for the first time showing a biological basis for the

disease that sets it apart from other neurodevelopmental disorders.

One of the reasons SPD has been overlooked until now is that it often

occurs in children who also have ADHD or autism, and the disorders have

not been listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual used by

psychiatrists and psychologists.

“Until now, SPD hasn’t had a known biological underpinning,” said senior author

Pratik Mukherjee,

MD, PhD, a professor of radiology and biomedical imaging and

bioengineering at UCSF. “Our findings point the way to establishing a

biological basis for the disease that can be easily measured and used as

a diagnostic tool,” Mukherjee said.

The work is published in the open access online journal

NeuroImage:Clinical.

‘Out of Sync’ Kids

Sensory processing disorders affect 5 to 16 percent of school-aged children.

Children with SPD struggle with how to process stimulation, which can

cause a wide range of symptoms including hypersensitivity to sound,

sight and touch, poor fine motor skills and easy distractibility. Some

SPD children cannot tolerate the sound of a vacuum, while others can’t

hold a pencil or struggle with social interaction. Furthermore, a sound

that one day is an irritant can the next day be sought out. The disease

can be baffling for parents and has been a source of much controversy

for clinicians, according to the researchers.

Elysa Marco, MD

“Most people don’t know how to support these kids because they don’t fall into a traditional clinical group,” said

Elysa Marco,

MD, who led the study along with postdoctoral fellow Julia Owen, PhD.

Marco is a cognitive and behavioral child neurologist at UCSF Benioff

Children’s Hospital, ranked among the nation's best and one of

California's top-ranked centers for neurology and other specialties,

according to the 2013-2014

U.S. News & World Report Best Children's Hospitals survey.

“Sometimes they are called the ‘out of sync’ kids. Their language is

good, but they seem to have trouble with just about everything else,

especially emotional regulation and distraction. In the real world,

they’re just less able to process information efficiently, and they get

left out and bullied,” said Marco, who treats affected children in her

cognitive and behavioral neurology clinic.

“If we can better understand these kids who are falling through the

cracks, we will not only help a whole lot of families, but we will

better understand sensory processing in general. This work is laying the

foundation for expanding our research and clinical evaluation of

children with a wide range of neurodevelopmental challenges – stretching

beyond autism and ADHD,” she said.

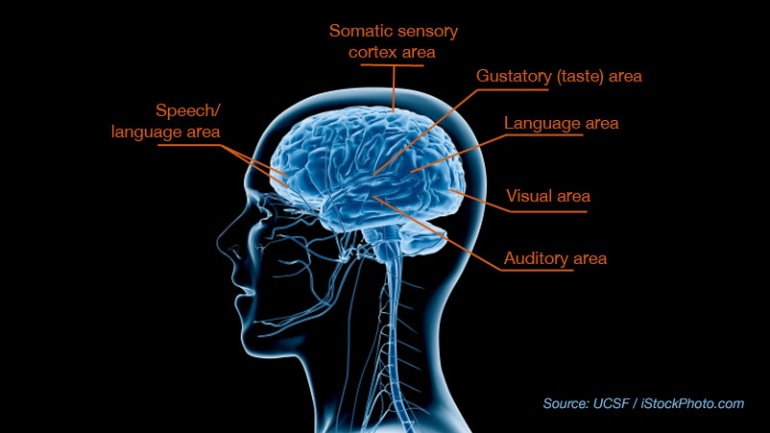

Imaging the Brain’s White Matter

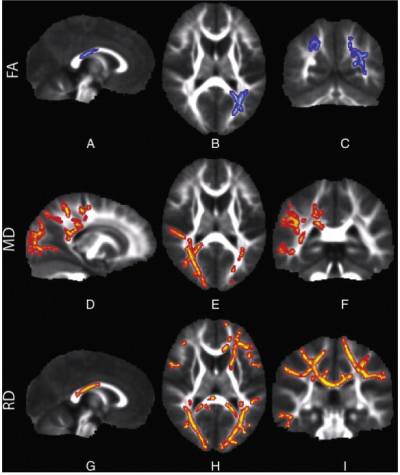

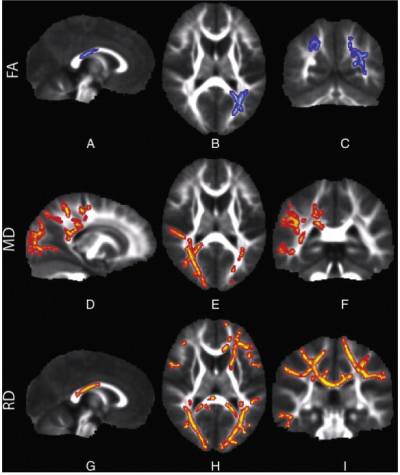

In the study, researchers used an advanced form of MRI called

diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which measures the microscopic movement

of water molecules within the brain in order to give information about

the brain’s white matter tracts. DTI shows the direction of the white

matter fibers and the integrity of the white matter. The brain’s white

matter is essential for perceiving, thinking and learning.

These brain images, taken with DTI, show water diffusion within the

white matter of children with sensory processing disorders.

Row FA:

The blue areas show white matter where water diffusion was less

directional than in typical children, indicating impaired white matter

microstructure.

Row MD: The red areas show white matter where

the overall rate of water diffusion was higher than in typical children,

also indicating abnormal white matter.

Row RD: The red areas

show white matter where SPD children have higher rates of water

diffusion perpendicular to the axonal fibers, indicating a loss of

integrity of the fiber bundles comprising the white matter tracts.

The study examined 16 boys, between the ages of eight and 11, with

SPD but without a diagnosis of autism or prematurity, and compared the

results with 24 typically developing boys who were matched for age,

gender, right- or left-handedness and IQ. The patients’ and control

subjects’ behaviors were first characterized using a parent report

measure of sensory behavior called the Sensory Profile.

The imaging detected abnormal white matter tracts in the SPD

subjects, primarily involving areas in the back of the brain, that serve

as connections for the auditory, visual and somatosensory (tactile)

systems involved in sensory processing, including their connections

between the left and right halves of the brain.

“These are tracts that are emblematic of someone with problems with

sensory processing,” said Mukherjee. “More frontal anterior white matter

tracts are typically involved in children with only ADHD or autistic

spectrum disorders. The abnormalities we found are focused in a

different region of the brain, indicating SPD may be neuroanatomically

distinct.”

The researchers found a strong correlation between the

micro-structural abnormalities in the white matter of the posterior

cerebral tracts focused on sensory processing and the auditory,

multisensory and inattention scores reported by parents in the Sensory

Profile. The strongest correlation was for auditory processing, with

other correlations observed for multi-sensory integration, vision,

tactile and inattention.

The abnormal microstructure of sensory white matter tracts shown by

DTI in kids with SPD likely alters the timing of sensory transmission so

that processing of sensory stimuli and integrating information across

multiple senses becomes difficult or impossible.

“We are just at the beginning, because people didn’t believe this

existed,” said Marco. “This is absolutely the first structural imaging

comparison of kids with research diagnosed sensory processing disorder

and typically developing kids. It shows it is a brain-based disorder and

gives us a way to evaluate them in clinic.”

Support SPD Research

Thanks to groundbreaking work from UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital

San Francisco, a biological basis for SPD has been discovered. There is

much work to be done and a funding gap. We still need to:

- Understand the genetic causes of sensory processing differences

- Uncover risk factors for SPD

- Measure the neurologic brain differences in affected individuals

- Determine if current interventions are truly effective for brain plasticity

- Develop new therapies based on scientific evidence

You can pave the way for a new era of sensory research and therapies by supporting UCSF’s scientific sensory processing team.

Learn how you can help.

Future studies need to be done, she said, to research the many

children affected by sensory processing differences who have a known

genetic disorder or brain injury related to prematurity.

The study’s co-authors are Shivani Desai, BS, Emily Fourie, BS, Julia

Harris, BS, and Susanna Hill, BS, all of UCSF, and Anne Arnett, MA, of

the University of Denver.

The research was supported by the Wallace Research Foundation. The

authors have reported that they have no conflicts of interest relevant

to the contents of this paper to disclose.

UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital creates an environment where

children and their families find compassionate care at the forefront of

scientific discovery, with more than 150 experts in 50 medical

specialties serving patients throughout Northern California and beyond.

The hospital admits about 5,000 children each year, including 2,000

babies born in the hospital. For more information, visit

www.ucsfbenioffchildrens.org.

UCSF is a leading university dedicated to promoting health worldwide

through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the

life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care.